The Grand Section Guardian #016 - Stop 16 Laverton/October 23, 2017

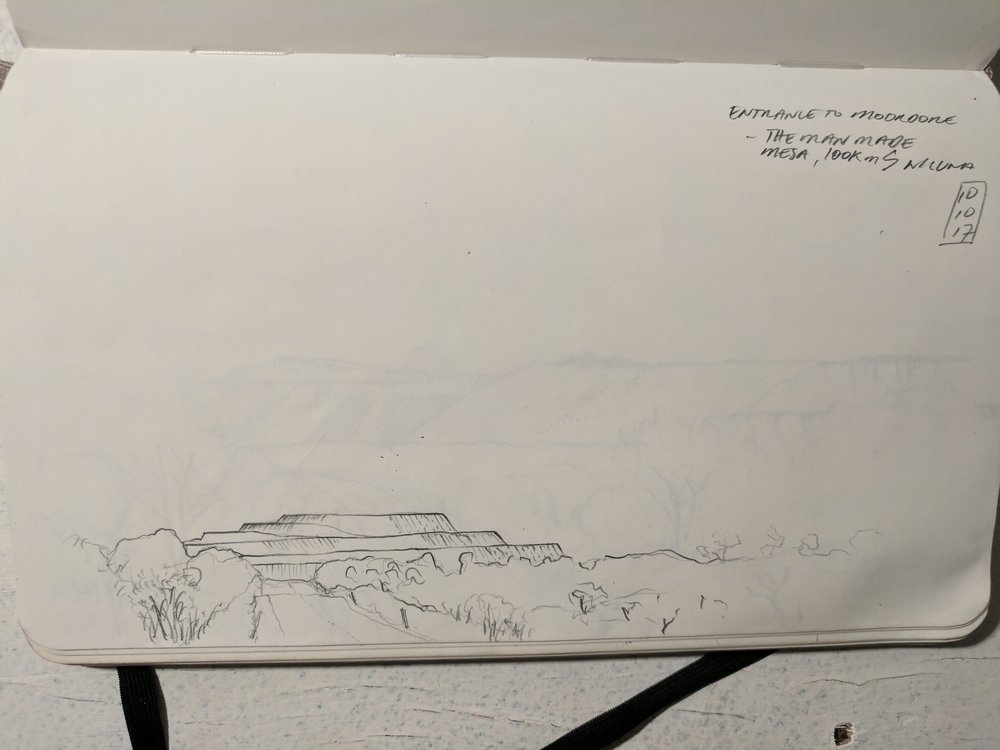

Littered in history and holes, it almost feels as if no piece of ground has been left untouched. Rusty cans, glass and broken prospector dreams litter the landscape. Manmade mesas and hills rise high above the Mulgas. Behind a clump of Acacias is a century old brick cricket pitch, overgrown. To the unknowing eye, simply, a landscape of ‘nothing’.

One thing to consider: Gold exists in greater abundance in Australia than any other place in the world. [i]

PLACE

24th September – 4th October 2, 2017

Laverton is situated on the geological basin, The Yilgarn Craton, known to be some of the oldest earth (along with Canada) in the world. It is believed the area remained above sea level [ii] for a bloody long time and experienced minor erosion due to the subtropical latitude, minimal glaciation and generally flat topography. Composed of approximately 2.8 billion year old granite, greenstone, and tholeiitic basalt and volcanism belts there is a huge endowment of gold mineralization throughout.

Home to traditional owners, Wangai (Wongi/Wangkathaa) the region covers the entire Goldfields area which once stretched from Esperance on the South WA coast as far north as Wiluna (above Laverton). As mining and pastoral settlement grew, the indigenous people were forced closer to camps and settlements.

Most settlements were located due to proximity of gold or other mineral deposits so unlike many other towns whose locality overwrite important indigenous sites, Laverton does not….well as far as we know.

Laverton (Lay-ver-ton, one mustn’t mistake it for the VIC, Lav-er-ton), locally referred to as “L.A”, is located in the rightly named ‘goldfields’. It has the closest grog shop for communities and towns since the WA border. The region of WA where many have passed through, building towns out of the dust, laying rail lines across desert-scapes and searching for fortunes.[iii]

The area was damn attractive to explorers with a long list attempting the ruthless landscape and their luck in the goldfields. The first successful white fella into this area was John Forrest, he travelled through the area in 1869 in search of the remains of Leichardt (another explorer who met a sad fate). First attracted in the 1870’s/80’s for its Sandalwood resource, cutters then quickly turned to bright eyed prospectors when gold was discovered in the area in 1886. First named British Flag (after the first gold mine), the efforts of a local doctor, prospector and bike rider, Dr. Laver was responsible for the current name ‘Laverton’. The township gazetted in 1900 was once a bustling hub at its peak of approx. 3000 folk, but succeeding only at the whim (as it still happens) of the gold economy correspondingly declined with low prices of gold in the 1960’s.

The infamous Nickel discovery known as the Poseidon boom in the late 60’s, for 20 years saw a RE-influx of infrastructure, services, houses and town redevelopment where in 4 months a share price inflated from $1.85 to $285, crashing overnight in its return.[iv] There has been much development in technology over the decades and so now ‘gold nuggets’ are no longer what the industry is after. Gold deposits of 1-2 grams per tonne of rock is seen as economical to mine and the going currency is ounce (32 grams and about $1600). That means to get one ounce of gold, 16 tonnes of rock needs to be mined (extracted, crushed and extracted) equating to approximately a 6.4m3 area. [v]

WA mining brought in houses just as quickly as they’ve now disappeared as prices and changes in mining operations now utilize ‘fly-in-fly-out’ FIFO workers with private airstrips, six figure salaries and fully catered donga villages with laundering, bars and dining halls with five different flavours of ice-cream to choose from. Very little of those six figures now see the local towns such as Laverton, money gets earned and taken back to the coast as quick as the roster rotates. Empty residential blocks, vacant buildings and a population of 300 are representative of another time reflecting these intricacies of the modern mining world.

With no permanent natural water sources, the life source is tapped into from below which is hypersaline due to the age of the craton. Bores allow permanent water sources, where those and water filled open cut coal mine pits still provide the towns water today. One particular water filled open cut coal mine pit is known as ‘the wedge’ or the town’s swimming pool.

"The Wedge" or as otherwise know the local swimming hole.

People

Jim Carter, Former Coach House Owner

Jim being a casual badass. Pulling "The Red Cross Emergency Desert Crisis Pack" lunch out of the back, we were overwhelmed, especially with its deliciousness!!!

Jim is one of those rare treasures who a short term tourist, without interest in the quiet, dilapidated, old building off the main street, would never have the pleasure to meet and enjoy his company. Arriving in Laverton in 1989, the man is an encyclopedia and walking archive of the town and more particularly The Coach House, which he refers to as “My Building”. He has devoted his waking moments to the building, no doubt many a sleepless night also. Responsible for enlisting the building on The State & National Heritage Register he owned the building for a period running a newsagent & bit of everything store. Due to this he observed closely the changing times of Laverton and the fluxes in the gold mining economy and its influences.

We were lucky enough to spend a few mornings with Jim and his amazing knowledge, even getting a tour of some of the more forgotten sites on the fringes of the town. Jim drove us around in his retired, red, Land Cruiser firetruck at a frightening speed, maxing out at 60kph (after the bikes this is hyper speed). We would stop next to a hole in the ground, or a barely discernible strip in the grass where Jim would proceed to pull out a folder of images and explain the history of the place, tell us tales of the pub, cricket matches and characters who carried pistols on their hips and shunned standard safety procedures.

At one point Jim pulled out a bat and ball from some secret compartment and we had a quick 20/20 match on the 115 year old Beria cricket pitch. Score; Bobbie: 4, run out by Carter, J in the first over.

Carol & Mal, Managers Laverton Caravan Park

Immediately upon meeting Carol and Mal you feel an overwhelming sense that your relationship is already rocketing to a great start. A warmth and genuine interest in every person who comes through their front gates permeates it’s presence throughout the shared kitchen and communal toilets!

Dinner with the Managers, Carol and Mal, the best roast we have had in about 7 months!

Travelers themselves, now grounded for the past 18 months and meantime managers of Laverton Caravan Park much to its fortune. They understand the nature of being nomadic and a life on the road, it makes all the difference. Their continual presence (be it from walking their dogs to cleaning, pottering and tinkering) and great attitude promotes a calming reassurance to all guests. Proof passive surveillance is one of the strongest tools for safety and cohesion one can employ. Along with the high standard they operate at and hence the park reflects this, the pride and respect they have for their guests and the park demands such in return.

The lethal duo habitually encourage guests to socialize and come to know one another of a Saturday night at their own expense. Fire side, they instigate anything from spud night, soup night or a sausage sizzle where they provide all condiments, bread and free BBQ time. On the surface, an excuse to socialize, but deeper than that they know intimately the value of people getting to know each other and the invaluable multi-generational and cross cultural learning that only happens when travelling. Interestingly, it is typically only the people staying in the lower cost accommodation (like us scumbags) that socialize. If someone is staying in a donga they tend to stay there.

One afternoon Carol gave up her rare and well deserved time off to introduce us to the Laverton surrounds and its many abandoned gold mines and hidden treasures. Their adventurous spirit honed from months on the road has led them to explore tracks and treasures that the town has to offer. She showed us abandoned hand dug mine shafts, lookouts, early prospectors camps and wells dug by steam powered machines! Plus the epic swimming hole. What a treat!

Laurinda Hill, Great Beyond Visitor Centre Coordinator

Being the fifth generation of the ‘Hill’ family in Laverton, her heritage in the town dates back to its meagre beginnings in 1896.[vi] Still heavily invested and concerned with LA, Hill Family members play vital roles in the community from the shire to mining and local business including an ambulance driver. There is a deep investment and collection of local knowledge and understanding of the changing times of LA and Laurinda holds a great deal of it. Prompt to reply before our arrival, she was just as impressive during our stay with her support and quiet patience as we’d return daily asking more questions as they arose.

Stuff (architecture)

Max Freeland’s words hold poignant and strong in reference to LA’s architecture. Also a reference that Troppo used in the reflections of their 1977 journey in Influences in Regional Architecture.

“…every building captures in physical form the climate and resources of a country’s geography, and the conditions of its society… Every building explains the time and place in which it was built.” [vii]

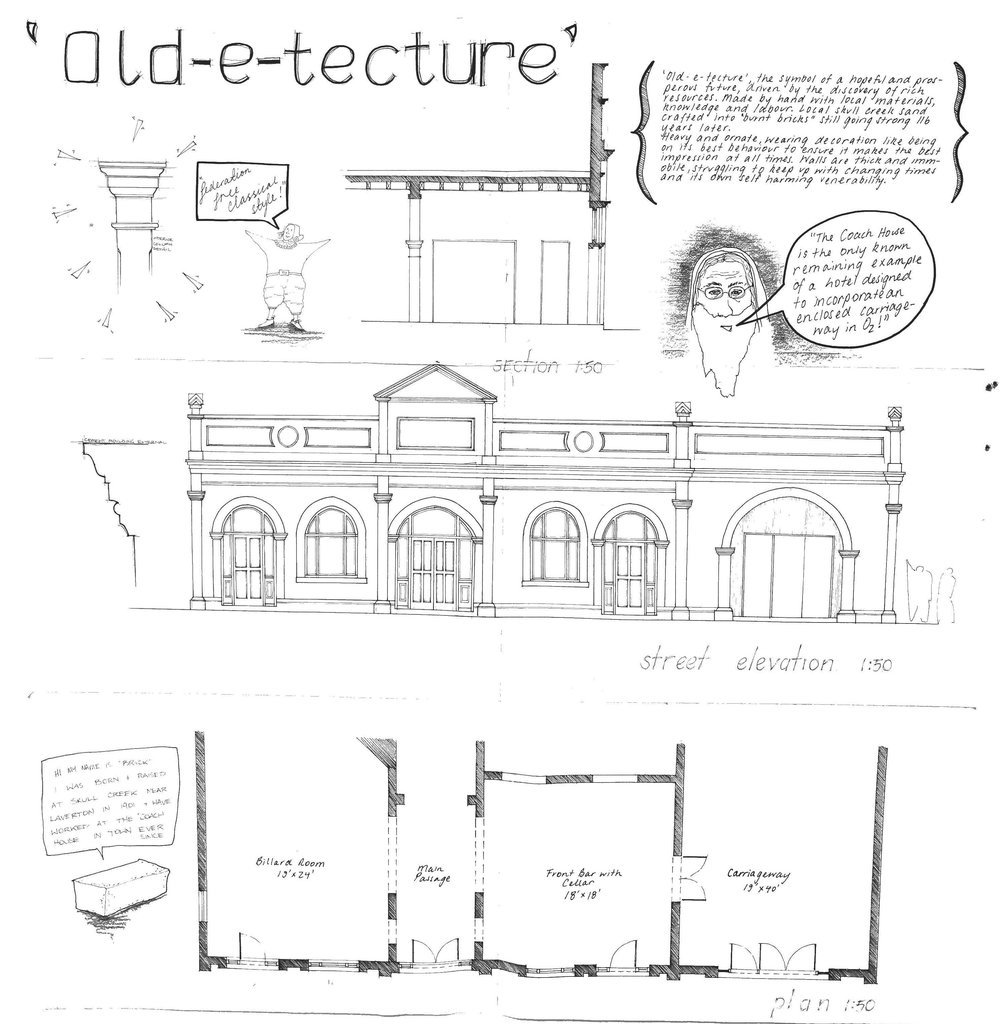

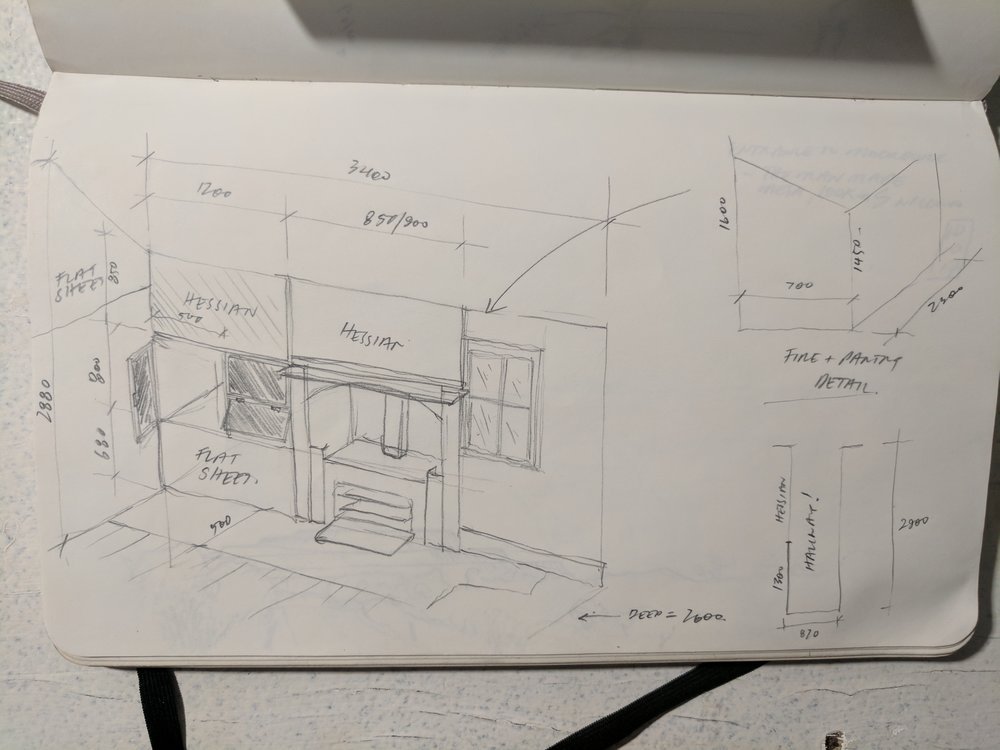

Mostly vacant or run down the buildings resembling the beginnings of the goldfields region and the gold fever is an aspirational style of architecture. Permanent in its presence, always central, invested in the place, a destination for the residents comprising the peaked population. They also tell of an invisible town plan which once transects the present main street, buildings that used to present a grand façade and toward the main street now face open space and other buildings soon to be demolished. A remnant of a time where mining was often done by individuals on small plots whose lives could exist on the goldfields, drinking and socializing were the favorite (and sometimes only) pastimes. Architecture was a symbol of what could be aspired to. Regardless of the location, the colonization approach dictated aspirational European inspired architecture.

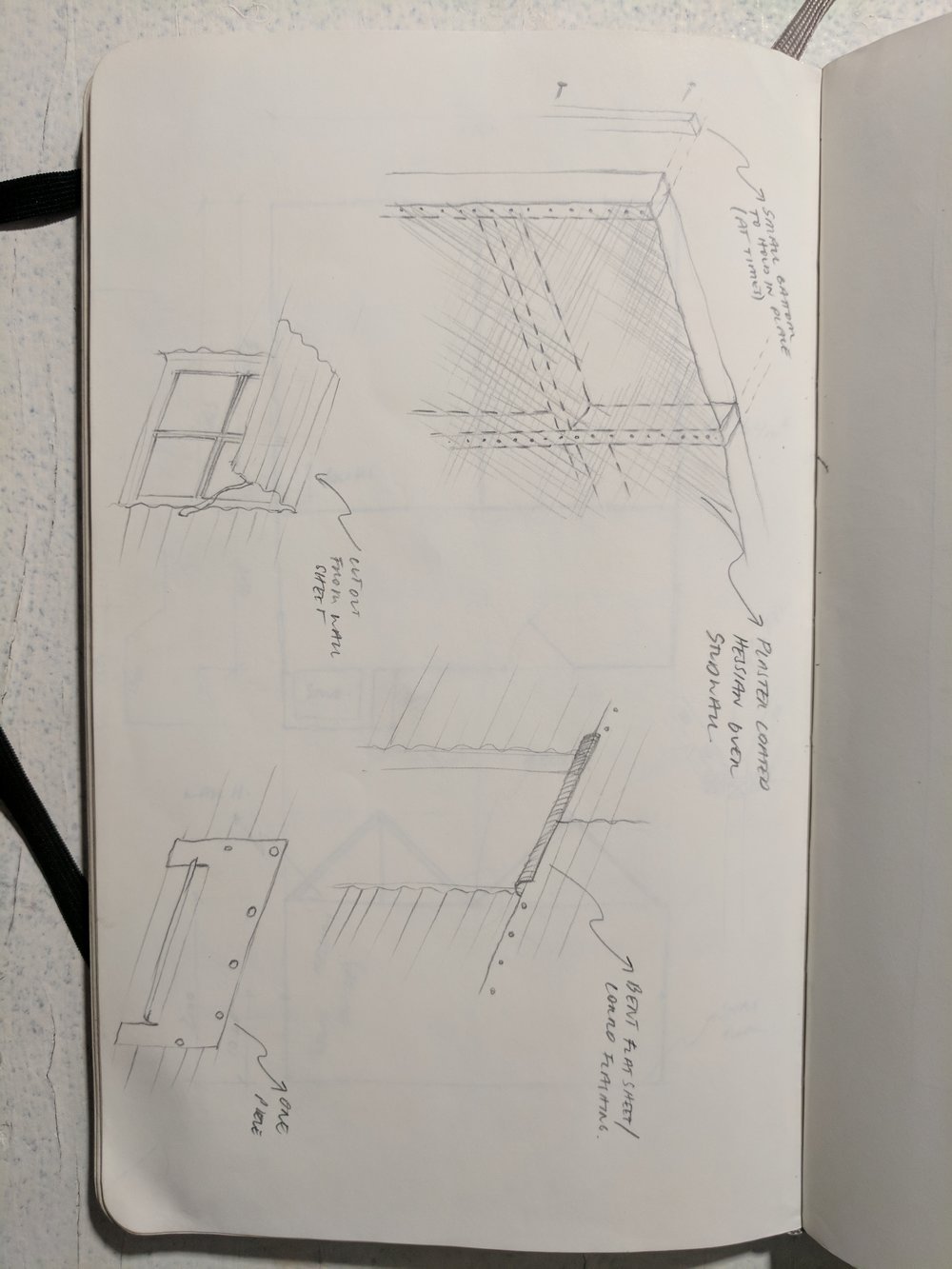

The most notable is The Coach House or ‘Jim’s Building’ and boy did it tickle our fancies. Built in 1901, of a ‘Federation free classical style’ (whatever that means), it’s the only known remaining hotel in Australia designed to incorporate an enclosed carriage way. Single-story brick, stucco, corrugated iron still with original pressed tin ceilings and half painted and filled in wall murals and adorned arches. Now orientated toward a grassy lawn (once the main street) it tells of a changed town plan as these grand old buildings typically fronted the main street.

The Coach House as it stands today, slightly forgotten and slowly crumbling.

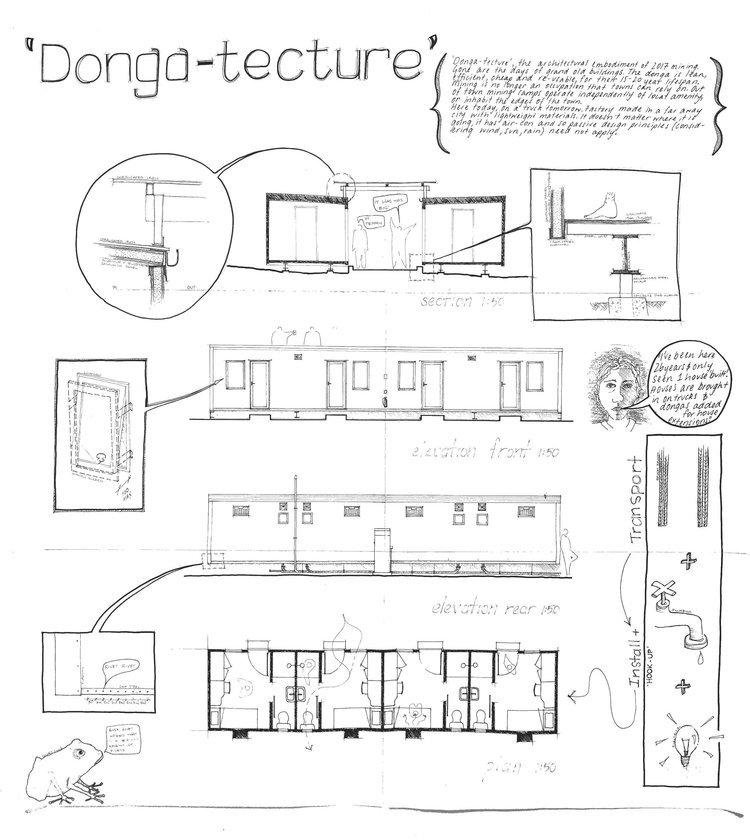

Conversely, contemporary mining architecture comprises of “Dongas” or “relocatable”, pre-fabricated buildings that come in and out on the back of a truck. Attach plumbing and power and you are good to go. This approach to architecture is almost the complete opposite to the 1901 approach. Architecture is merely limited to the time frame of the mine. Fly-in-fly-out work now means towns are no longer needed. Entrepreneurs aiming to attract customers with fancy buildings need not apply here. You don’t need a pub if you have a “wet mess” on site and have to “blow zero” tomorrow morning anyway (zero blood alcohol level). Tightly planned, fabricated in a factory with rivets (also used in airplane’s) and available anywhere. Passive solar design or cross ventilation aren’t needed if you have air-con and are only there for two weeks. Even when these Dongas are used within the towns they are commonly found on the fringes. Seemingly the temporary nature of these buildings also detracts from their ability to add meaningfully to town centers.

We were told by a local that in the 26 years she has resided here, she has only seen one house ‘built’. It is typical for houses to be bought in on the back of trucks from further afield or dongas ordered as “house extensions”. Most houses we saw were transportable. Be it the few 70’s dated asbestos sheeted houses or modern weatherboard and lightweight construction.

Some of the older buildings are incredible in their solidity and aspiration however they are also prone to becoming heritage items. Things can be somewhat of a two edged sword. Whilst the heritage status awarded to them attempts to protect them from easy demolition or non-sensitive alterations ensuring longevity, they can be put into the “too-hard basket”. Its venerability becomes almost self-harming, impeding perceptions it can keep up with the changing times. In order to use these buildings, strict guidelines have to be adhered to, which makes using buildings a step more complex. For instance, with The Coach Houses, because of its heritage significance, apparently there are only five contractors in Australia who are ‘allowed’ to work on the building!

There is probably no straight answer to this heritage predicament but something needs to be put in place. These small towns, their buildings integral to Australia’s history are crumbling. Left unused with a future, unsure.

Outside the mining architecture of Laverton we were struck by one big landscape feature. Fake grass. Used prolifically throughout the town. Covering the large roundabout at the north end of the town, the areas used by indigenous as a hangout spot opposite the council and in patches of public space where a bit’o’green spices it up. When we questioned people about this the common response was that it was too hot for regular grass and maintenance with water was too expensive. Grass is more than just a plant, it’s a status symbol.

Another big aspect of Laverton was the ‘Wood lines' which were light, narrow gauge tramways which ran miles into the bush to collect cut timber and bring it to their central depots. Steam powered machines, fires and underground mines needing props and struts for structural integrity meant huge amounts of wood was needed from somewhere. As landscape became denuded, the wood Lines ran further and further afield. Cutting would average about five tonnes/acre where wood line companies at their peak were delivering around 1500 tonnes of timber per day[viii] to the mines and towns (about 30 semitrailers). It was one of the largest industrial uses of timber for fuel anywhere in the world in the 20th century. The men who worked on these lived in “camps” which were transported by rail and along the wood lines. Once at location these Hardwood timber framed with corrugated iron cladding structures were lifted into and out of place by man power. How bloody great! Imagine if today one could grab their mates and shift a house just so... Goes to show 'donga' style living isn't a new phenomenon. It begs the question, how much does your house weigh?

Today all that remains of the 50 or so mine sites many with associated townships are ruins or holes in the ground. Easy to miss or mistake for a natural formation. Jim Carter’s 15 years of study on the subject is incredible and encyclopedic. The technological advances in mining now leave only mountains and valleys behind, manmade geography.

Exhibition, Saturday 30th September

Flat pack architecture, cheap, economical. Architecture in palatable form, bite size slices. A contrast similar to ordering a margarita vs. a dripping meat lovers, our work exemplified either end of resource influenced architecture; Old-e-tecture vs. Donga-tecture, the contrast of LA’s 1901 architecture with its 2017 counterpart, the frugal younger sister. Displayed in take away pizza boxes, portable and lightweight, just like a donga.

Sat in the Information centre the day after the AFL grand final, about three tourists walked through the doors so we presented to the staff and a few locals who were also hanging about getting a coffee or milkshake. The tourists that did wander through glanced at our hopefully displayed pizza boxes and kept browsing through the post-cards and books on gold mining history. Always discussions leading ways we wouldn’t expect and deeper into discussions about architecture and Laverton life. Following our info centre stint we rode over to Jim’s house – pizza boxes under arm. A one on one presentation across the dining table. It instigated a great dialogue surrounding the nature of both types of building. After a quick nap on the communal lounge donga sofa we emerged to the Saturday night sausage sizzle and ended up taking around the BBQ tables with some of the other caravan park guests. A fantastically ad-hoc and informal way of engaging in Architecture.

Suggestions

Ensure the impacts of heritage don’t mean a building won’t be used. Take Renew Newcastle as an example of how to breathe life into buildings in the interim of their disuse

Consider the lifetime of the building your constructing, how old will it grow to be? How long will the materials last? 116 years like The Coach House, or 60 like many suburban homes today? What then?

If Dongas are the choice, build in a way that’s reusable, relocatable &/or recyclable... what about biodegradable!? The biggest mark we should leave on our landscape is our shadow.

Bring back the parapet. (We should make that into a T-shirt)

Re-use and convert the huge, abandoned holes that will never be filled in. More town swimming pools? Water reserves? Inland marine parks? Rally-ways? Go-kart tracks? Mars training grounds? Amusement parks? An ambitious wishing well? World’s best ball pit? Abandoned open cut pilgrimage walk? Inverted sky scraper?

In-between (Laverton & Meekatharra)

Wednesday 4th - Thursday 12th October

HOLY CRAP!!! WHAT IS THAT GREEN AND BLUE BIT!?? Getting close, we're in sniffing distance! incredible landscape scenery as the bird sees it.

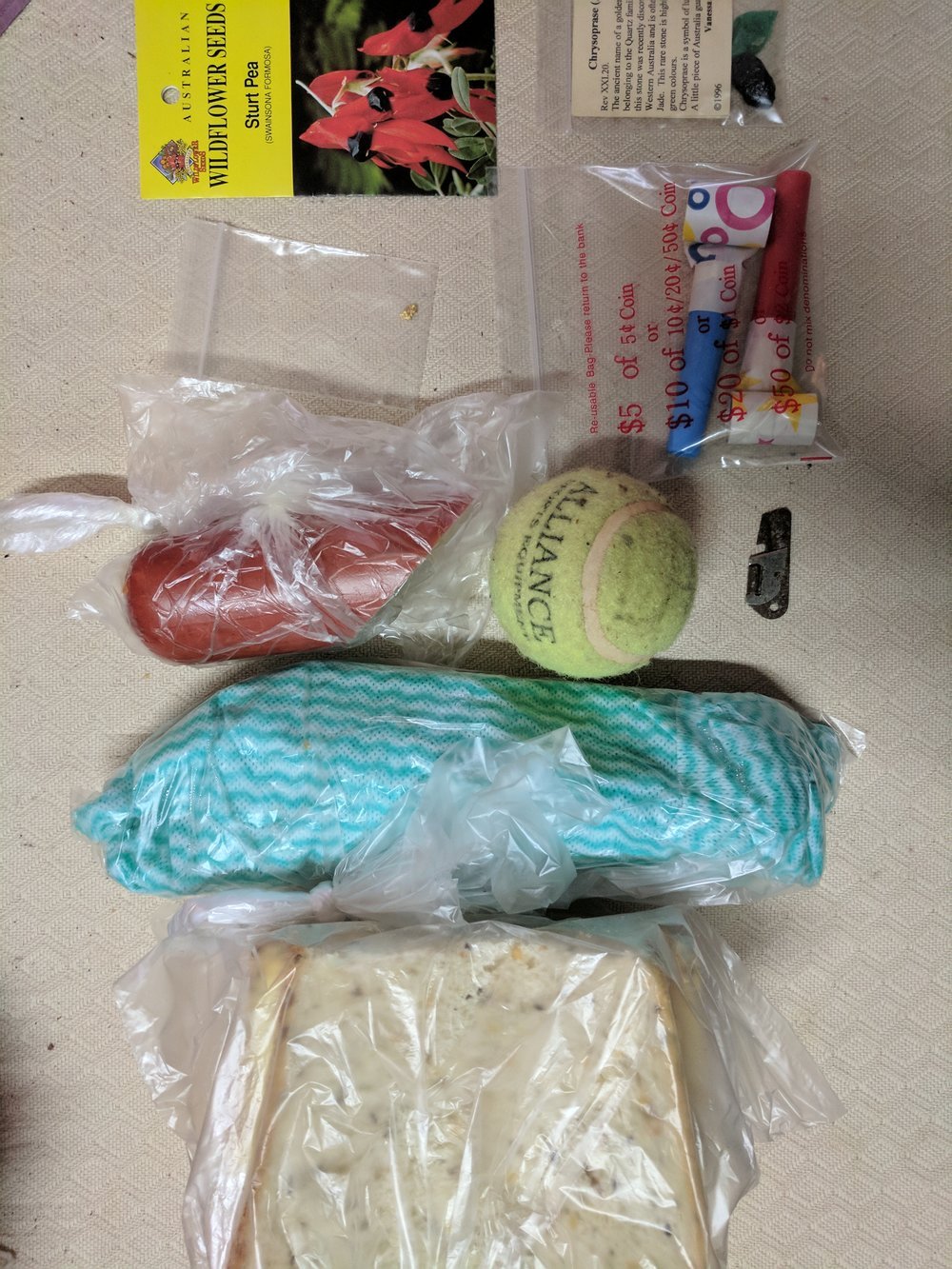

As we cycled out we dropped by Jim’s one last time, to bid farewell. Excited by our presence he had carefully laid out incredibly thoughtful gifts for us to part with. Amongst a generous offer of a lift due to the ominous weather he gifted us with things such as a small nugget of gold he had once dug up, a tektite as Bobbie had carried on about their beauty days prior, two slices of freshly baked and buttered bread and some party blowers for our arrival into Carnarvon, eventually. On a high, we began our ‘in-between’ cherishing the friend we had found in Jim and feeling elated.

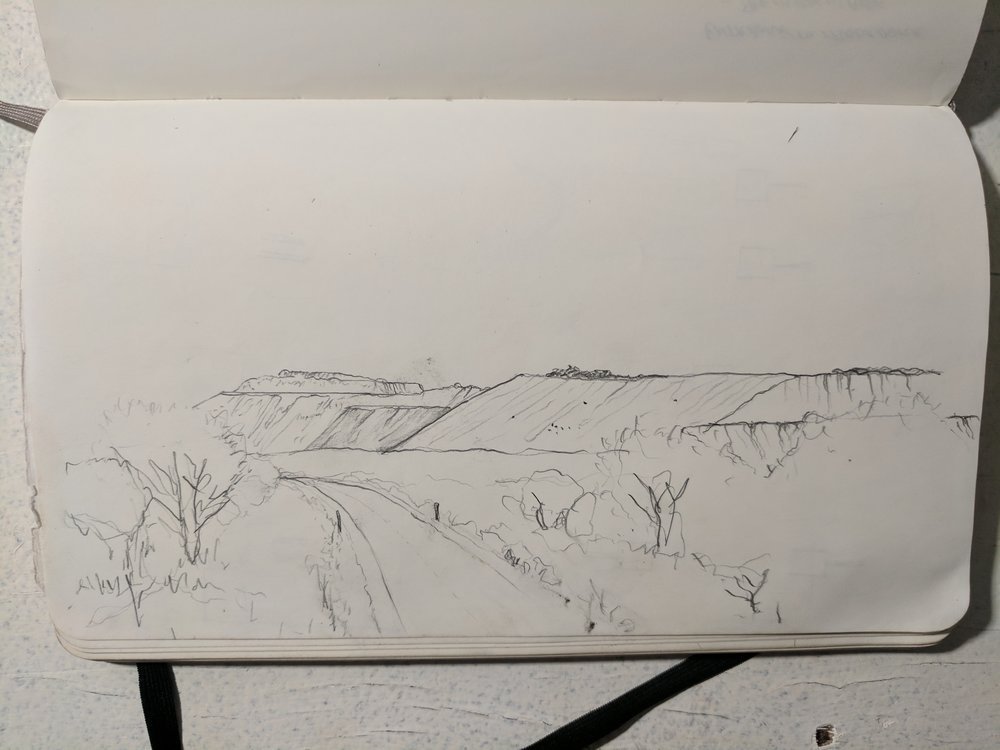

Rain has been a rarity during the trip, especially throughout the centre. Nonetheless, it finally found us as we were departing Laverton, storm, thunder and wind included. Worried about the caking dirt roads we decided against the scenic route through abandoned mining towns and almost forgotten history, unfortunately. As an exchange, we followed the appropriately named Goldfields highway. Four dog trucks (semi-trailers with four trailers), some 53 metres long were our best company. Carrying ore, sulfuric acid and who knows what, at least 20 would pass night and day. Mining being a 24 hour operation, always a low hum radiated across the landscape from the many mines, with us coming to appreciate the real meaning of ‘noise pollution’. In the still of the night, you could hear the trucks about 3.5 minutes before they passed, sounding similar to a jet plane taking off. There were traces of the industry everywhere; tyre tracks mowing over trees, water finding new paths eroding landscape, bits of tyre every few kilometers, huge pipes appearing and disappearing into some-where and signs alerting the presence of high pressure gas lines below. The most astonishing though, the man made mesas rising above ANY natural feature. Millennia of geology upturned, piled and bare.

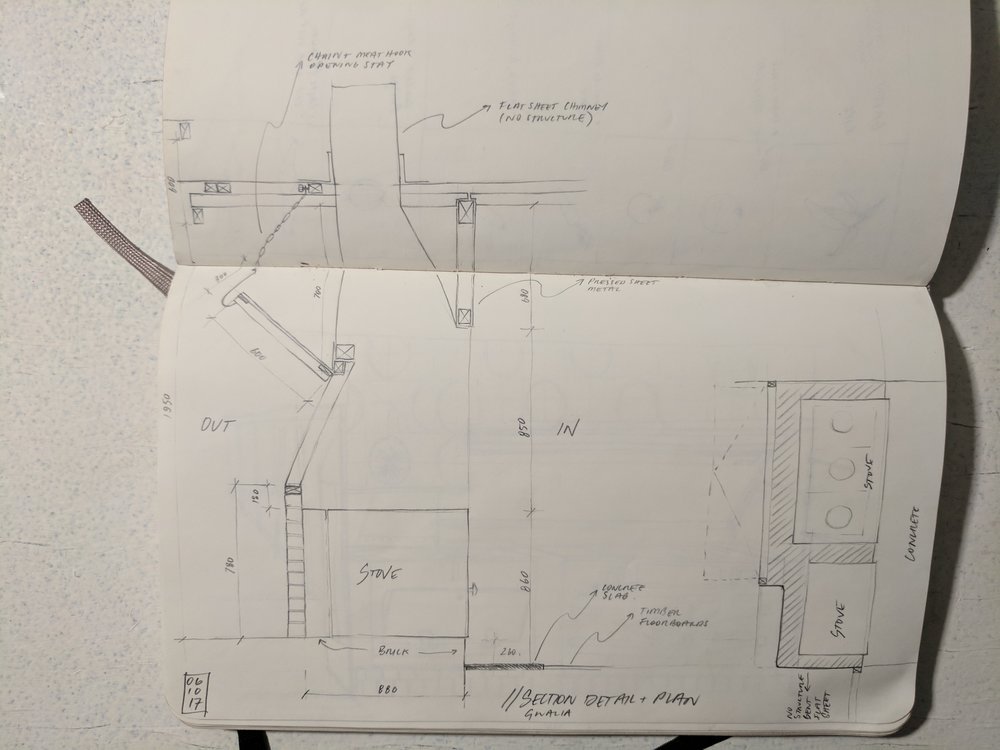

The end of Day two saw us into Leonora, another mining town. Approached by a keen 81 year old man intrigued, (also an opportunist) he was quick to offer showing us around the abandoned town of Gwalia, two miles (3.2kms) south – where it all started. Bob Biggs, growing up during the peak of the town rode the lines from age 12 covering for drunken and ill workers, a boys dream as he seemed to recall it. In 1963 the mine closed, overnight the population moved on, buildings left abandoned and the same for free classical federation style pub (only brick building). Similar story of the goldfields, resource dictating everything. Bob though encouraged us to camp in the buildings and so took up a room we did.

The contrast though of these details amongst the spring landscape was almost incomprehensible. Wild flowers lined our paths; purple mulla-mulla and pussy-foot glistened amongst the silvery mulgas, red quondongs occasionally, and straw spinifex against burnt red friable clay soil. Bush bananas winded their way through hosts as did the harlequin mistletoe, the epitome of opportunists.

As planned, early Day five we finally rode into Leinster, a BHP funded town, for a shower and water top up. A weird place, a weird vibe. This is a BHP closed community, only for BHP employees and families are allowed to live. A small scrubby camp site for caravans and the like costs $20 per night with a maximum stay of 14 days. Built almost entirely out of relocatable buildings, even the supermarket, Donga city. The supermarket for the well paid white fellas, was the cheapest and best stocked we had come across in a long time, an interesting comparison to the other shops in similar areas whose main clientele are often the poorer Indigenous people.

![Incredible river red gum, adapt in this country or die (refer to reference [ix] for content)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/654deb2d4d3a7802ec176855/1704559224380-92JHJH1YWO50E6I1959D/IMG_20171006_134247.jpg)

Day eight saw us into Wiluna for another top up. Home to the story of the last nomads, two Mandildjara elders were brought here after being retrieved from the desert. Arriving at 8am ready for the shop to open, we were just in time to hear the shop side of the doors being unscrewed by a power drill in order to open them. Wiluna was meant to be our 16th stop, however, the lack of a place to stay and with pressing documentation & university work (amongst the slowness, ha) we rode on to Meekatharra. Really starting to feel trip fatigue of 7.5 months of ‘going’ (more so mentally than anything) the tail wind over the next two days was an absolute welcomed blessing. Allowing us to cover 100kms + both days. We arrived in Meekatharra on Day nine for the usual, beer, coke, chips, gravy and buttered, white (shit) bread. Shower and rest. There is nothing carbs can’t fix.

[i] www.minerals.org.au, Rush, Australia’s 21st Century Gold.

[ii] www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1440-0952.2002.00912.x Regolith geology of the Yilgarn Craton, WA: Implications for exploration, R R Anand & M Paine

[iii] www.abc.net.au/goldfields/history/?section=about

[iv] www.laverton-outback-gallery.com.au

[v] From a great geologist we befriended in Laverton Camp Kitchen, 1m3 = 2.5 tonnes approximately. It costs approximately $1600 to mine 1 ounce (32grams) of gold, $1000 processing cost and so hence a $600 profit.

[vi] Lgfocus.com.au

[vii] Max Freeland’s, Architecture in Australia: A history 1968)

[viii] http://museum.wa.gov.au/explore/wa-goldfields/environmental-impacts/woodlines)

[ix] "Slowly does it", we say!! Taking the time to traverse landscape slowly has been one of the most valuable tools we've employed during The Grand Section. Yep, hugely challenging on the mind and body we admit, but the reward is coming across rare ancient giants such as this 10m girthed river red gum. It's been a long time since we've come across anything remotely large. On the north bank of a dry creek bed about 14kms north of Leonora WA, this gum is acting as a mallee or Moort as they call it in the west. As gums are dictated by light, the similarly aged multiple trunks have ducked and weaved over many decades, usually an expression of shallow soil. The bulbous root is possibly a similar adaptation for storing food to cope with the dry seasons. With an annual rainfall of 150mm, the goldfields country (as with most of central Australia) is dry and the answer to survival is ADAPT or DIE! Thanks to our east coast landscape expert Craig Burton for entertaining our endless questions! We think understanding landscape is just as important as architecture!

Edited by Jen Richards! Thanks Jen!