The Grand Section Guardian #015 - Stop 015 Warburton/October 3, 2017

Ride in, dusty and lunch hungry. Time turns back 1.5 hours so the pre-prepared lunches don’t come out for another hour, delayed further by a drop in internet and EFTPOS services. Camp dogs and dust clouds from ever cycling windowless cars. Lunch when it does come is a surprisingly tasty burger, the only hot and filling option. It’s the off week for fresh food, a couple of sad carrots for dinner. Nothing unusual.

PLACE

7th – 17th September

Located in the semi-desert area to the south of the Gibson Desert and the north of the Great Victoria Desert lies the Brown and Warburton Ranges (commonly called the Ranges). Nestled at the base of the Warburton range is the town ship of the same name, with a population of about 500 it is the largest town/ “metropolis” in the Ngaanyatjarra (pronounced NANG-AN-JIRRA) lands. 548 km east of Laverton and 558 km west of Yulara (Uluru) this place has some serious remote credentials. It is this remoteness and the apparent lack of resources that has also helped to preserve the cultural and ecological qualities of the place. Warburton we’ve noted is also the turning point, where resources from this point no longer get delivered and transported from the east (Adelaide, Alice Springs) but now come from the West, from Perth!

'Warburton Cage style' transcends to petrol pumps too. Unlocked, administered and always attended by a roadhouse worker

Able to “boast” some of the harshest conditions for inhabitation, this area had the lowest population density anywhere on the planet, small groups of less than a dozen people relied on mobility and a fine tuning to their environment to survive[i]. Elder Creek near Warburton was one of the places where after good rain a larger gathering could occur. A vital place for cultural and social interchanges.

The Ngaanyatjarra lands at 159,948 km2 are comparable to England [ii] in size. The town itself is just back from Elder Creek, after being relocated 5kms due to a flood (a familiar story) during its missionary beginnings. Originally established in 1934 by William & Iris Wade of the United Aborigines Mission, rations were given to the locals in exchange for dingo scalps that the missionaries traded for money in the goldfields town of Laverton. This allowed the purchase of the rations for the locals and to establish the school, church, dorms and hospitals taking children into their care. In 1961 Aboriginal parents decided to care for their children in their homes and missionary dormitories closed.

By the mid 1960’s effects of long drought, the clearing of the Woomera Rocket Range along with the promise of food and blankets brought 400-500 aborigines to reside in Warburton. In the 1970’s with changes in government policy tending focus from assimilation to self-determination Warburton formed an Aboriginal Council taking over administration giving itself autonomy. It is still managed by the Ngaanyatjarra council today.

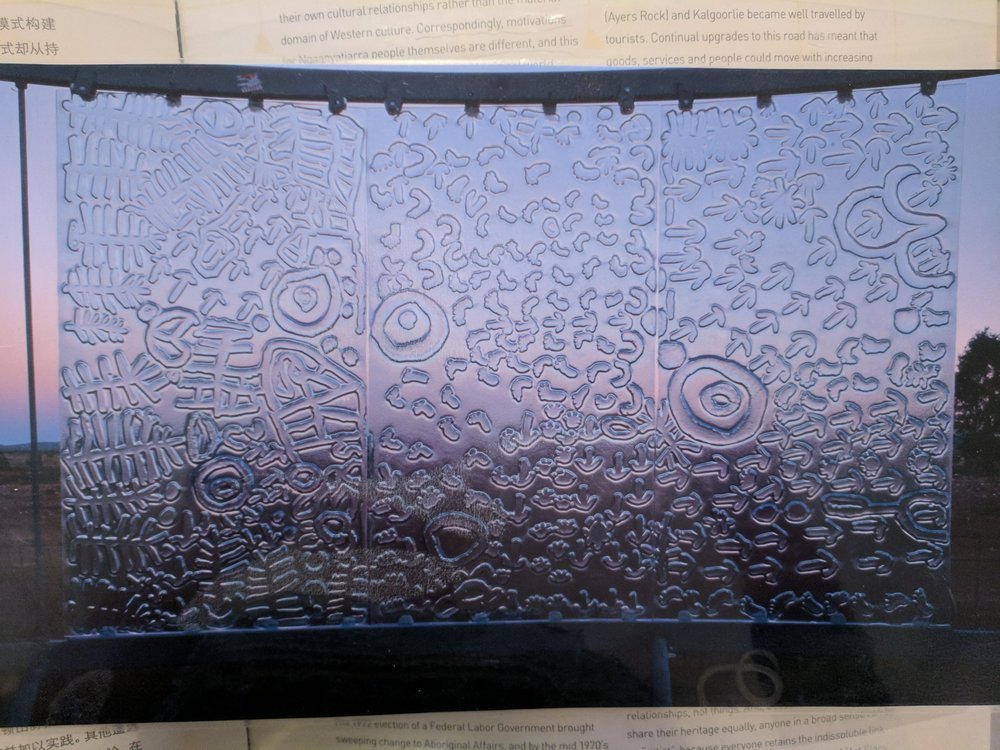

Warburton is surprisingly home to THE LARGEST collection of Indigenous art in Australia that is held by Aboriginal people themselves although remotely under the radar amongst the red dust, beginning in 1989, this is a pivotal collection of over 900 pieces for people of the Ngaanyatjarra lands and Australia, ensuring the preservation of cultural history due to its documentation. Essentially, a strategic depository for cultural knowledge[iii]. How bloody excellent!

People

We’re coming to realize it’s the people of a place which makes the experience and Warburton is truly comprised of some crackers! Ngaanyatjarra lands still house Ngaanyatjarra people, a rare and valuable detail. A people not entirely displaced from their land, the beauty of what remoteness and ruthless landscapes can preserve. Living continuously on their traditional lands, Ngaanyatjarra people have not experienced direct dispossession from their country [iv]. Ceremony and language are still strongly practiced by the local populace.

In saying this there is still a clear segregation between white and black. Not just in the fenced in white-fella tourist park on the other side of town but within the town itself. Interaction between white and black is limited beyond the day to day activities and town services run by the white-fellas. Casual social activities appear to stick to racial groups whereas organized cross cultural events see some casual interaction but without on-going social relationships. A similar circumstance that we have seen since Alice Springs, a lack of a ‘space’ encouraging and allowing a cross-cultural dialogue.

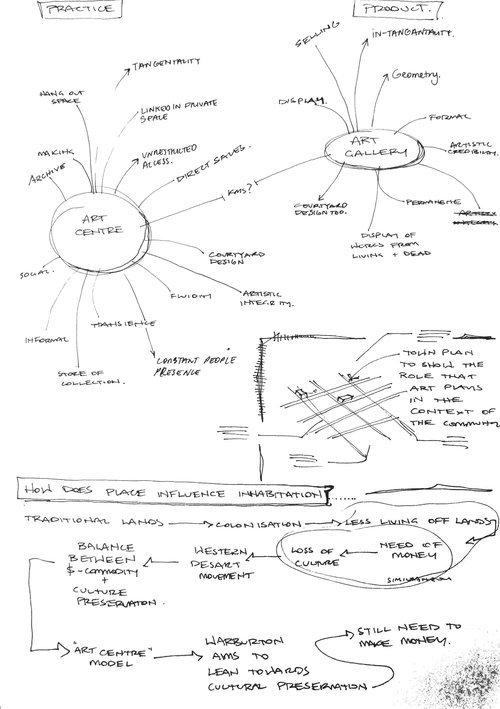

Gary Proctor (Curator/Coo-rdinator, Warburton Arts)

Thinking around this space for the past 30 years, the man is a force to be reckoned with. Moving out to a bush camp near Warburton in the late 80’s Gary has been pivotal in establishing and continuing the documented and extensive Warburton collection and hence the ongoing preservation of Naangantjira culture. Gary’s house for many years has been the Art Centre of Warburton, a place to paint, make, hang out and learn. Creating a space that is familiar and comfortable for cultural work to shine.

However being his home there is a sacrifice of personal space to achieve this. Gary has an energy and passion that is rare and tangible, this was an experience in itself. Getting shown through the Warburton Art Gallery was a tour-de-force (Warbo style) that opened up painting like books. Gary’s passion for Ngaanyatjarra art and culture is unbridled and his understanding deep from the many years of elders imparting stories and cultural content.

Not content with the market driven model of Aboriginal art & artefact prolific through the western deserts of Australia, Gary and the Art Centre has championed diverse art forms, preservation of the best works for cultural heritage and pushes to go beyond traditional audiences creating a broader dialogue. Warburton’s main medium is canvas and acrylic dot paintings, however in the collection includes carving, weaving, pottery, photographs, glass and textiles. A large slump glass kiln sits in one of the rooms off the central courtyard and is responsible for some of the most tangible works we have seen. The potential, artistically and architecturally is HUGE.

Mon Sanderson

Working at the Art Centre as well is Monica, a film graduate and social worker trained art-a-holic. She supports the artists in their work, takes plebs like us around town, fires glass and documents the art collection to name but a few jobs in her huge scope of works. She expressed the value and benefit of her social work background, whilst being in an art role, dealing with people she can often be left managing and navigating through complex social and cultural situations. Whilst Gary’s energy draws you in it is Mons quiet strength and laughter at the idiosyncrasies of desert life that allow her to navigate the occasionally land-mined territory of the Warburton art scene. Welcoming us as if old friends, her warmth and hospitality truly made our time along with her willingness to entertain a constant barrage of questions.

Danni, Dan & Tom (Community Development Prgramme, CDP workers ‘work for the dole’)

L - R: Owen, Tom, Mon, Dan, Danni, Andy (mon's dad) & Bobbie

Essentially working with mandated clients, these guys are achieving brilliant things and it’s in the most part due to their attitudes and approach to their work. Credentials as a school teacher, a builder and a handyman, in charge of the “work for dole” group this trio’s days consist of anything from making cups of tea to cutting open the roofs of cars. Their shed in the centre of town, dubbed “the college” is testimony to their sensitive and open approach. Before this trio began (eight months ago), the maximum term for a worker was three months where constant vandalism and damage to The College was a reflection of this.

This crew has now transformed the place, bringing new ideas, motivation and energy along with their own spare household goods to encourage the users (ranging from small babies to elderly women) to create ownership and pride of the space. Their efforts have created a comfortable and friendly environment that encourages people to attend their work for the dole commitments creating ownership and pride over the space along with identity, vandalism has lessened to almost nothing. Again, one of those familiar spaces. People are invited to move furniture, paint on walls or supported to follow their own projects (like fixing cars, or growing plants). Whilst perhaps people shouldn’t need encouragement to get money from the government, attendance is in constant flux and often a challenge. If a person doesn’t attend they can be cut from their welfare payments for up to eight weeks. When you live in a community where everyone knows everyone it can have some pretty heavy repercussions for extended family, services and the like when this occurs. Adding to this, cultural obligations such as funerals and business mean people sometimes have to leave communities for extended periods or suffer the social and cultural shame, a powerful force. We take our hats off in respect of these people and their incredible work.

Noted as crucially important by all of this crew is the support they provide each other. Being able to come home and talk to someone who knows what you have been going through. Serious mind-games are common with manipulation and unstable characters prolific. There is an eloquently worded ESSAY by Kim Mahood on this that explains it far better than we can. Without this household of support, Mon, Dan, Danni and Tom don't think their experience would be nearly the same.

Stuff (Architecture)

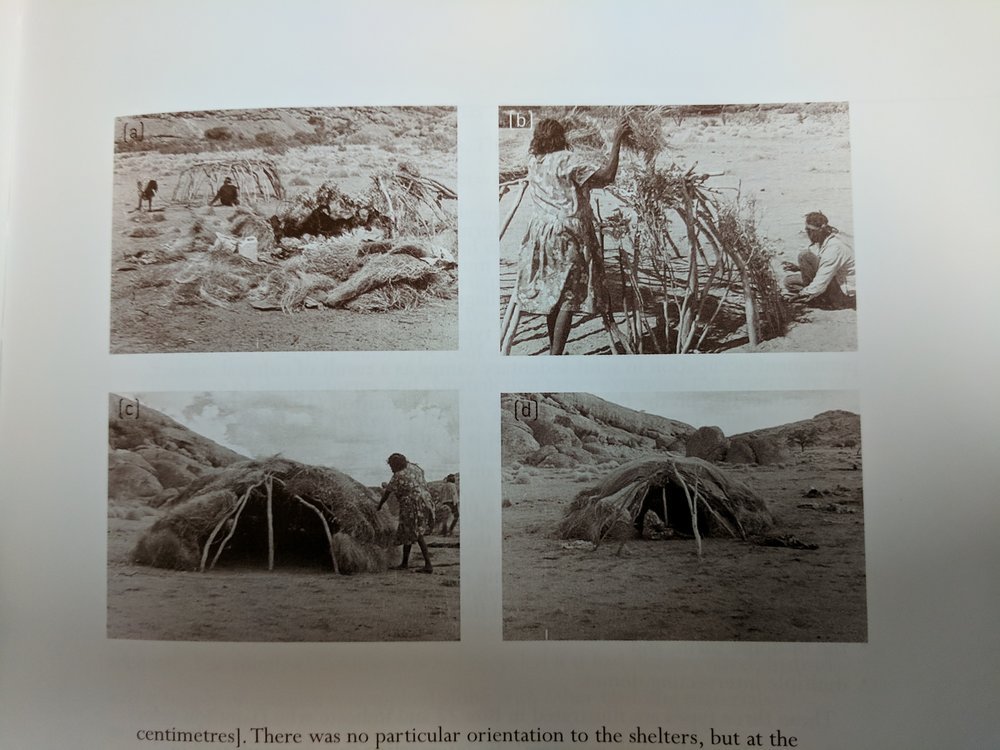

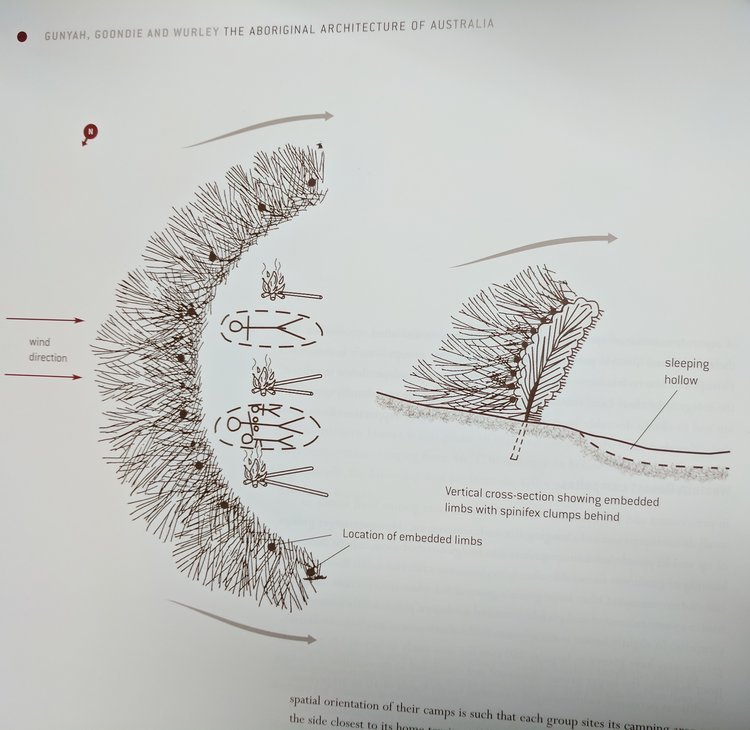

The indigenous architecture of the area was dictated, as always, by what was available and how far groups had to move for food and water. Windbreaks of Mulga and Spinifex were common and often the only form of shelter. Small warming fires helped people stay warm during the night, however having to get up every 20 minutes or so to stoke a fire doesn’t seem like a great night sleep. Windbreaks also gave options for interaction, slouching could indicate wanting privacy whilst sitting upright showed interest. Semi-enclosed shade structures were also probably used, referred to as ‘wiltja’ meaning shade these lightweight rigs also used mulga and spinifex but provided some more protection. It is reasoned that the required distance to travel for water and food meant that more substantial dwellings would be superfluous[v].

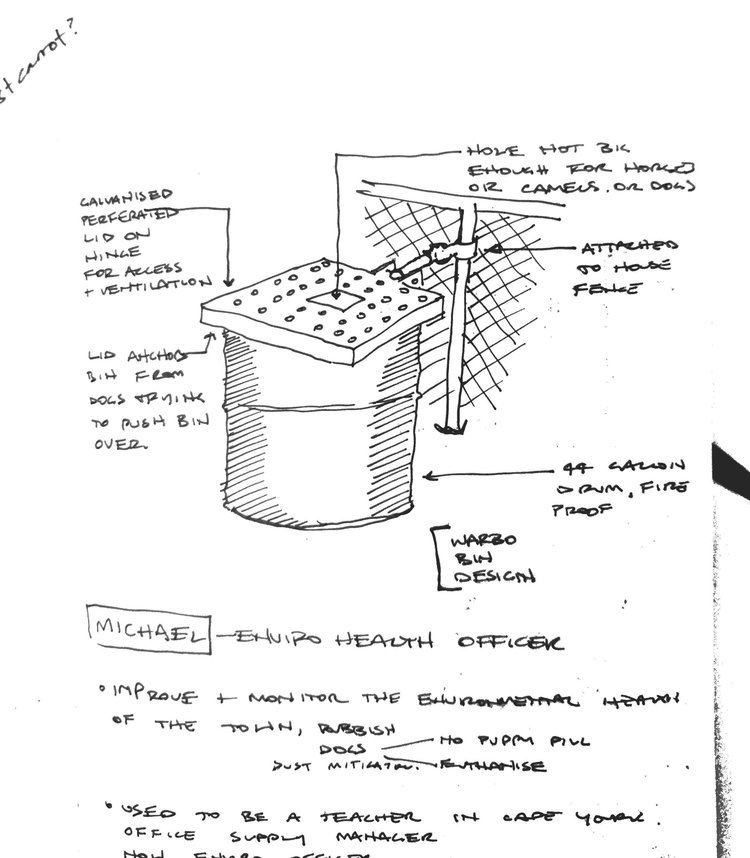

Warburton today is not dissimilar to indigenous communities we’ve seen and come through; the Roadhouse fenced in high with razor wire atop, same for the nurses’ compound, houses and street lights in cages. Materials here are pushed and tested to their limits, perfect product testing grounds. Bessa block, concrete and corrugated iron are the predominant construction materials. Robust, hard wearing and resilient to hold up to the use, occasional vandalism (predominately kids and only if they didn't like the people), weather and climate.

The international “Warburton Cage Style” was prolific. Yard fences, verandah fences, dead bolted doors and even sometimes dead bolted bedroom doors. Security concerns are apparent, perceived or needed, only those living there would know. Opinions differ.

"Warburton Cage Style" - Dwellings are robust with layers of security separating inhabitants from the street. Bessa block, steel, concrete, corrugated iron.

Digging deeper, whilst there were some security issues with break-ins, the abundant security window screens were more for rocks thrown by kids. Actually one of the favorite pass times which we witnessed was to throw rocks at the ceiling of the old basketball court and see if you could puncture the already shredded fibre cement sheeting. The steel though, holding up a treat. Many houses had very little screening at all and talking to the owners (who were not at all worried), we were told that rocking of houses often depended on how you were perceived in the community. If you were liked well within the community you had less problems.

Whilst much residential architecture was cagey…the community buildings were often very open, still robust but far more welcoming. The low-fenced lime green church in town has a series of external shade structures, fire bins, a toilet block, and stage and P.A system in the front yard in the heart of town. This can be heard, turned up to 11 most Friday and Saturday evenings. Flexible and adaptable where movable seating and a speakers create a usable space that can be easily re-arranged to suit whoever wants to blast their eclectic 90’s music mix. We were told, the inside is almost irrelevant. It’s the outside, dirt and carpeted ground which is used. (see drawings on exhibition poster!)

On the other side of the Great Central road (and spectrum) lies Tjulyuru NgaanyatjarraCultural and Civic centre, or otherwise known to the plebs like us, The Shire & Art Gallery. Designed by Townsville based Inside Out Architects this impressive structure shows off the famous Warburton collection and holds the shire offices for the area. Made from rendered concrete block with a monumental courtyard design this bad boy is out of place in its sharpness of detail and planning. Almost a shock to the unwary traveller who elsewhere is used to community art galleries being tucked into whatever building was vacant at the time. However unlike the church the formality of this building does not invite you to stay and enjoy the carefully thought-out space. There are some politics behind this though that may mean the building hasn’t reached its final form. Regardless of those, the building creates a presence, is aspirational and gives further credibility to the cultural collection.

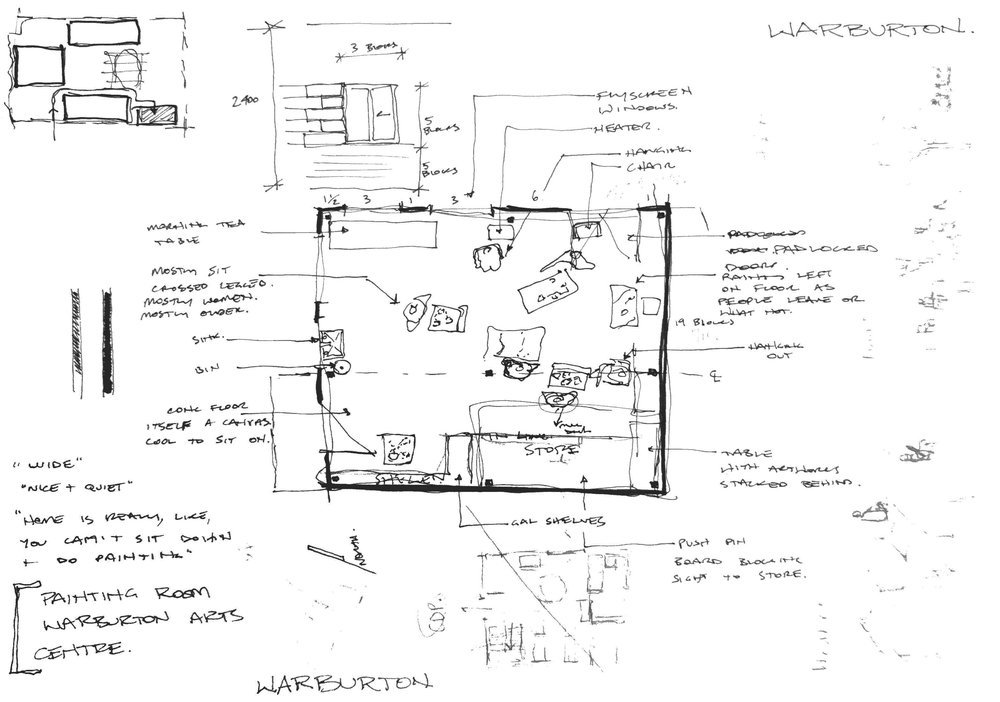

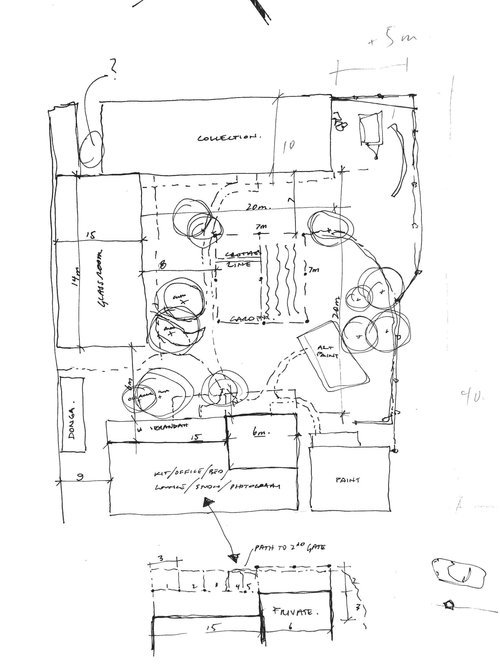

Back in Warburton proper the art for the gallery is made at the Art Centre, which Gary and Mon work out of. A mongrel of uses crammed into a residential block. Since Alice Springs we have been talking about, but not seeming to experience a space where black and white people can meet voluntarily and where people can be comfortable and for a variety of reasons. A space that helps with reconciliation and cultural understanding. The Art Centre as we witnessed seems to be a great precedent for this. A series of buildings of different uses around a central courtyard. Options of privacy, variety of uses and options of interaction create a space where ownership can be taken by the user easily and comfortably. Perhaps though one of the key aspects is the fact that there are full time residents/live in visitors who provide passive surveillance and a continuous reference point for people coming and going.

In questioning the local workers and delightful Police sergeant, Ryan about the presence of after-hours vandalism and if a building or infrastructure could assist in minimizing its prevalence (naturally as you think in Architecture a building is the solution….) we were responded with “maybe” along with the explanation of the nature of remote communities being hugely under-resourced and understaffed. With great youth services working activities until 9pm, there still is no ‘third space’ as it’s often called, other than home or school/work kids, teens and adults can go to after hours. No pubs, cafes, library’s. The answer first and foremost though is not necessarily a built one… shock horror!

Exhibition, Thursday 14th, September

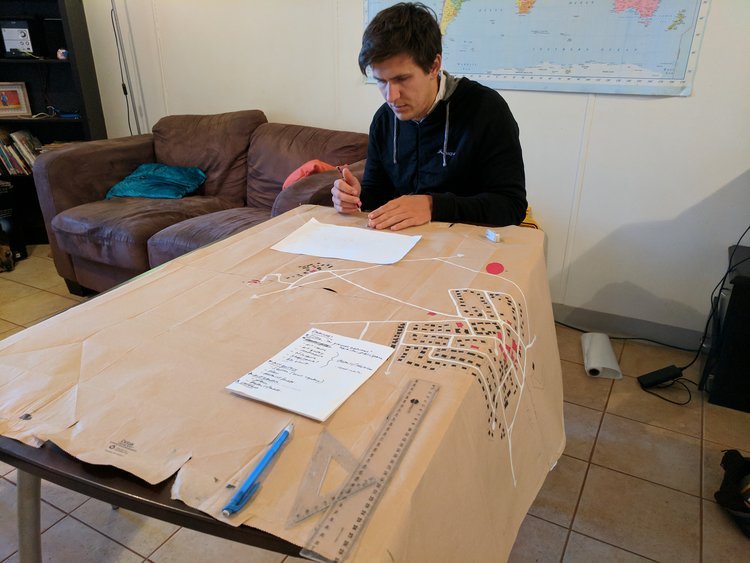

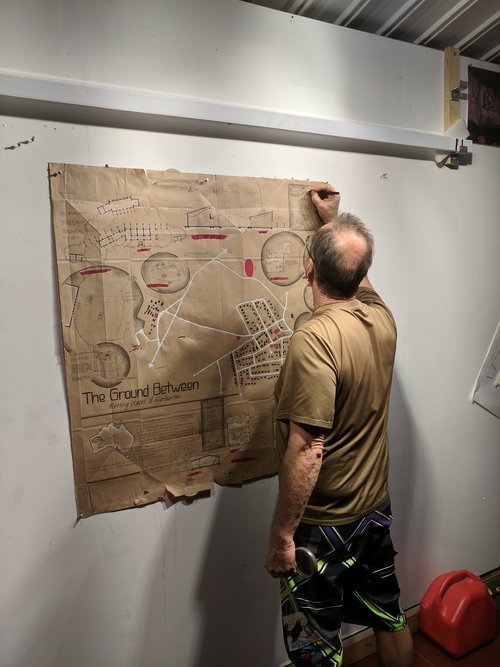

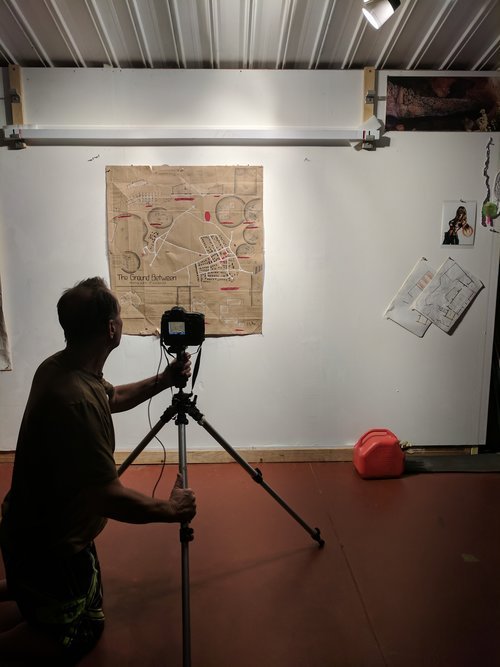

The exhibition poster

Taken by the fantastic space that The Art Centre is we decided to see if it was in fact architecture and the construction of the space which created such a successful meeting space or whether it was something more intangible. So, we looked broadly at the meeting places of Warburton from The Roadhouse to The Supermarket to The Church. What we found was that Architecture did play a role and through this were enlightened about how spaces were used.

Observations:

Options of edges, inside/outside, inside/views out, above/views down, sitting inside/outside, shade/sun, private/public was apparent and well used.

A familiar, comfortable space is optimized with autonomy e.g. Use of speakers

A variety of functions for a variety of interests strengthen a space

Permanent residents allow passive surveillance giving a consistency to space

Greenery, stops dust and provides shade. At the local football grand-final peering around the edges of the field locals were always ground SAT, UNDER TREE SHADE – cooking, watching, chatting, and cheering.

Drawn straight on to paper shopping bags, the exhibition was welcomed with great energy by Garry who proceeded to draw over, correct and amend our work pinned up at The Art Centre. Welcomingly we encouraged this, as it’s the locals who know and understand a place. In carrying out the data gathering and documenting of towns, their architecture and how they function across Australia we are happy to lose preciousness over our work to get it right (also a fantastic lesson in architecture and presenting).

In-between (Warburton to Laverton)

17th - 24th September

An eight day ride to our next stop, a road house 245 kms down the road and one birthday on the way. What a time to be alive! Departing on a Sunday we hit the road late after saying goodbye to all the incredible people who had helped us, we were helped out by a 26km stretch of bitumen just out of town and were surprised by Mon, her dad Andy, Danni and dog Bluey. Doing a few drive by’s back and forward armed with a go pro, Mon’s film degree and interest came to the forefront along with Danni’s exclamation, “we clearly have nothing else to do”. It was an absolute highlight, making the wind a little easier to bear.

Clouds thanks to strong winds were delivering stunning sunsets on the road. Hundreds of wrecked, abandoned and burnt out cars and stunning rock formations scattered the edges of The Great Central Road in equal quantities. Mulga, tea tree, mallee and spinifex scrub accompanied us along with out of place towering and budding bloodwoods.

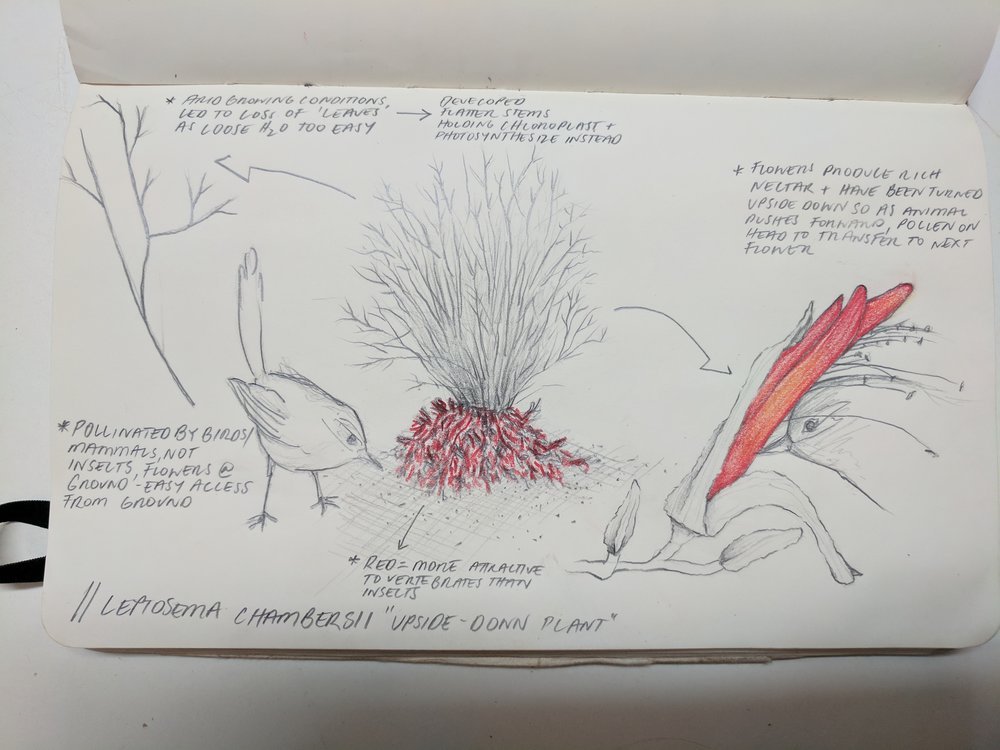

Moving now (at the beginnings of spring) from the Gibson Desert to the Great Victoria Desert wild flowers abounded with wattles of numerous varieties with yellow poached egg daisies, purple broad-leaf Parakeelya and white and pink fluffy mullah mullah’s dotting the road side. Bobbie has taken a great interest in understanding the flora we pass, in particular their adaptive traits in order to survive (to then transcend into 'architecture'). Something she has recently learnt and is stunned by is the unique mechanism in Eucalyptus to endure, depend on and recover from fire damage with the biome evolution dating 60-62 million years ago! Holy shit!

Dunes change to east west orientation as you head west and the deep red of the dunes is dominating although mostly covered in a skin of spinifex. Contrary to what the bloke from Docker River Camp Ground told us, it was not “just flat from here west”, lots of hills, rocky outcrops, Gnamma holes Holes and equivalent meant that the headwind that was roaring on the last few days was excellent…. (That’s Owen’s optimism).

We made it to Tjukayirla roadhouse, in four days, which also happened to be Bobbie’s birthday. That morning Owen treated her to a bouquet of desert flowers and the regular morning muesli in the tent, breakfast in bed equivalent.

Three days before Laverton the wind was unbearable. Hardly able to fight a peddle we were getting thrown off our bikes with sheets of dust whipping and covering us. We waited roadside taking cover for five hours till the evening when (normally) the wind dies down to do our last 15kms for the day.

It didn’t die down however riding in the evening is seemingly ‘context less’ due to a lack of visibility. Riding, you can’t seem to fathom speed, terrain or if you’re riding uphill or downhill so we go there amongst everything else that comes out at night; copious amounts of spiders and snakes.

Riding into Laverton, doing as we had done for previous days we were up by four am trying to avoid the wind picking up with sunrise. And so, riding in at lunch time we came across a pub! The first for us since Alice Springs, some 1500kms ago. We indulged in the much needed carb gorge; beer, hot chips, gravy and buttered bread.

Cheers,

Dusty & Thirsty

Edited by the bloody brilliant Jen Richards. Thanks again Jen. YOU BLOODY RIPPER!

References

[i] Connected to Country, essay, 2010, David Brooks, www.warburtonarts.com

[ii] www.warburtonroadhouse.com.au

[iii] Under the road, the desert essay 2010. Gary Proctor. www.warburtonarts.com

[iv] Under the road, the desert essay 2010. Gary Proctor. www.warburtonarts.com

[v] Gunyah, Goondie and Wurley, Paul Memmott, 2007